In 2002, I made a portfolio of 12 images called Dream House. It was originally printed in the New York Times Magazine, conceived and published in collaboration with the Magazine’s esteemed Director of Photography Kathy Ryan. Dream House was a unique project, in that it was and still is the only editorial commission I’ve done, and the only time I’ve featured well-known and recognizable actors in pictures in an overt and conscious way. The making of these pictures was a labor of love, and is a fond memory.

This is the second in a series of posts dedicated to the 20th Anniversary of this body of work.

AS ANYONE who has ever read about our pre-production process knows, we go to great lengths to plan every tiny detail for each picture before we ever get on set. There are meetings, consults, written descriptions, fabric samples, sketches, location pictures, lighting tests, and studies. But inevitably, despite all those efforts, there are always things that arise that are outside of our control. Part of what makes being in production exciting, in fact, is the way circumstance forces you to be in the moment, make quick decisions, switch directions if necessary, or pull the plug altogether on a picture if for whatever reason it’s just not working. In many cases, the problems, mistakes, and surprises result in the best pictures.

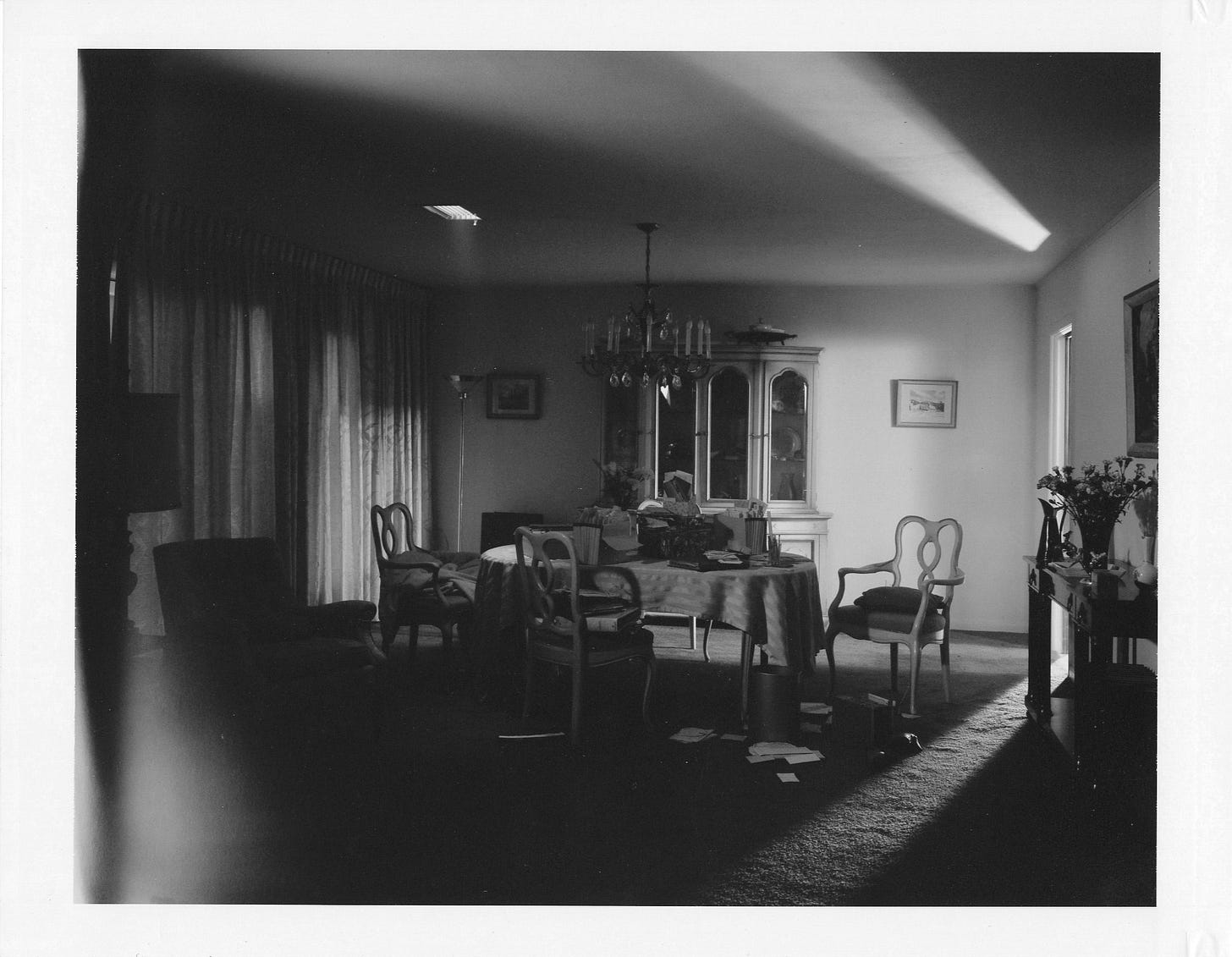

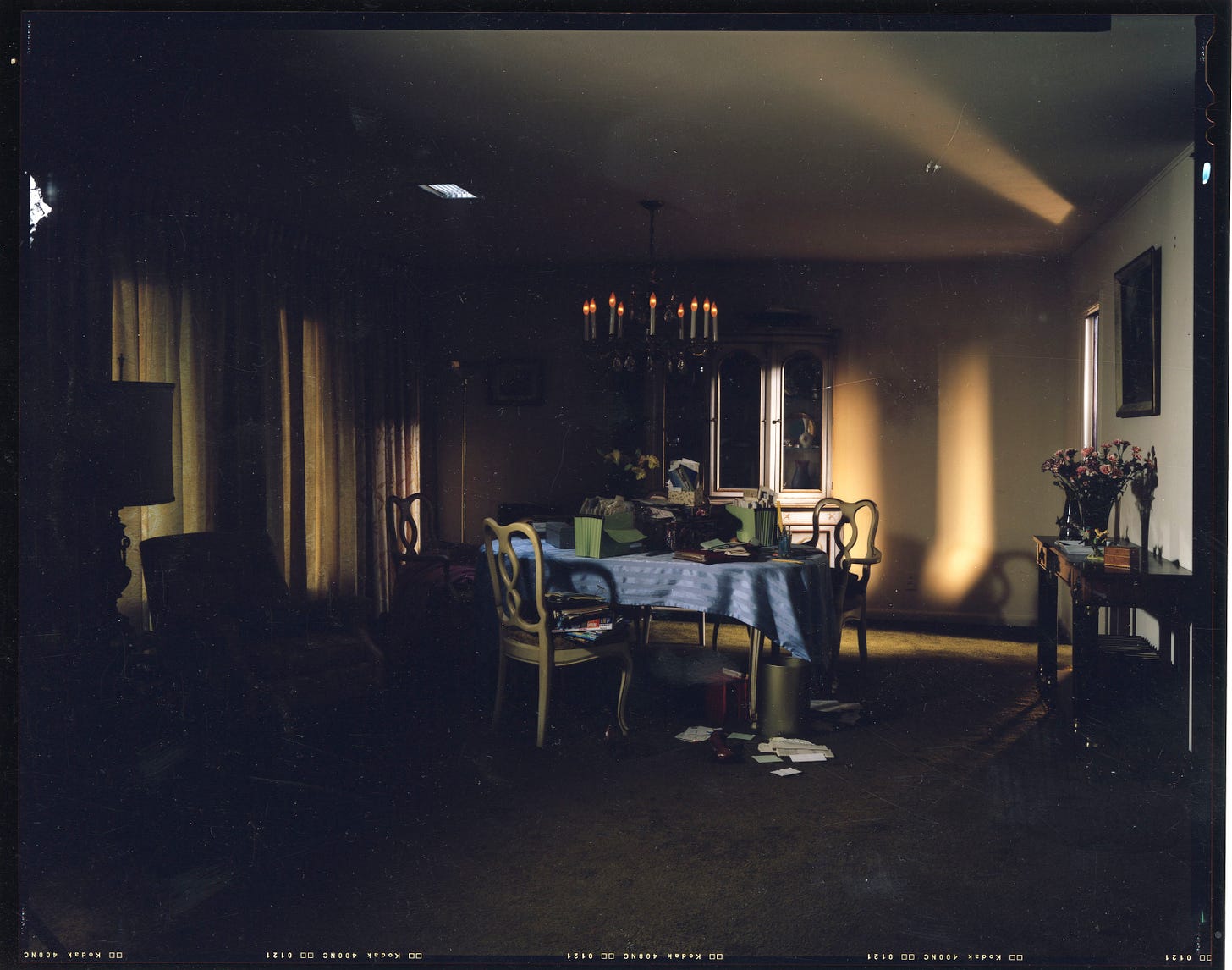

This was the case with the Julianne Moore picture in Dream House. I originally had a picture in mind for her set in a dining room. There was a vent in the ceiling that we made into a light source. On the table below there were flowers and gifts, and an ambiguous assortment of business papers and bills in disarray. Julianne is looking up toward something out of frame, lost in thought.

Below are some 8 x 10 black and white Polaroid studies I made for that picture.

We then made a series of test shots on the 8 x 10 camera (a couple contact prints are below,) but at some point, I knew I wanted to rethink her picture. So I made the decision to shift gears. I came up with a new concept in a different space, and the next day, we wound up shooting what turned out to be one of my favorite pictures in the series — Julianne seated on the edge of a bed.

The funny thing is that now, looking through the contact prints and Polaroids for the original set up, I can see that there was also the potential for a beautiful picture emerging. But had I not made the decision toward a new concept on that shoot I may not have made the picture that was clearly meant to be.

I wound up using the dining room for another picture featuring Dylan Baker, Becky Ann Baker, and their daughter, and a boy that we cast from the neighborhood. The light source in the ceiling vent became a central narrative element, with Becky Ann Baker having gotten up from a family dinner to gaze up at it. This turned out to be another of my favorites. Everything works out for a reason.

Editorial note: This piece was written by Juliane Hiam based on conversations and interviews she did with the artist.

Looking at your photographs, I experience the same intense pleasure as when I discovered the photographs of Olype Aguado, Achille Bonnuit, Humbert de Molard, François Brumery, Henry Peach Robinson and all the photographers who marked the beginning of this art. Perhaps, because photography by its original link with the theater (Louis Daguerre was first a painter before converting to the profession of theater decorator for which he executed remarkable paintings (in particular the decorations of Aladdin or the wonderful Lamp at the Opera) irremediably participates in "performance". Not only being a device for the mechanical reproduction of reality, it modifies it through lighting, recomposes it through the pose and arrangement of the decor, even invents it in "representations" life. It is thus part of the duration, not only by the recording of a moment forever suspended, but also by the time necessary for the preparation of the photographed scene. That this preparation is very brief (in the reportage: choice of subject and framing, parameters or automatisms) or longer (in life still photography: decor, lighting, role-playing of the actors, etc.), the photographer experiences the time. This relationship to time is enriched in the life still photography painting with a substantial temporal expanse, anticipating the shooting, which places it on the side of the story and the narration. The photographer therefore evolves in the imagination and draws the viewer into his time universe so complex.

Dream House is such a compelling set of pictures. Thank you for continuing to give insights into the making of your work. Was there something specific that didn't land in the early test images with Julianne or was it that they just didn't "feel" right?