I had an image in my mind of a figure floating in water years before I ever made Untitled [Ophelia] in 2001. The idea came partially from a dream, but some other specific references were, of course, the John Everett Millais painting from 1850, also John Cheever’s “The Swimmer,” and the haunting underwater scene in one of my favorite films, Night of the Hunter.

MASS MoCA, formerly Sprague Electric, opened as a museum in 1999 under the leadership of Joe Thompson. I was in touch early on with their curator Laura Heon, regarding a future show of Hover and Twilight. But I was not yet done with Twilight, and I still wanted to make my elusive Ophelia picture. Sometime in late 2000, use of the soundstage was offered to me. Larry Smallwood, the Exhibitions Manager and Technical Director at MASS MoCA at that time, became the project manager of the whole “Ophelia” endeavor (along with Sue Killam, who was General Manager at the time.) Larry and Sue would go on to be instrumental in dozens more pictures I’d make on their soundstage in the coming years. But initially, I only had that one picture in mind.

I wanted to bring the Ophelia theme into a domestic setting — build an ordinary suburban living room inside a tank, and flood it with water. I knew this would be a challenge, but I really had no idea just how complicated it would be.

I started discussing the logistics with Nick Thielker, a production designer who had taken the lead on many of the more complicated set builds leading up to that point: sod and flower towers, beanstalks, a 1/3-scaled house and garage placed in the center of a suburban street, among others.

The Ophelia set had many new kinds of considerations I hadn’t dealt with before. For one thing, I hadn’t considered just how heavy water would be. The depth of the water would have to be a bit of an illusion. That meant cutting down all the furniture by a third.

All the furnishings — everything in the picture in terms of props in fact — came from a vintage store in North Adams I had driven by many times. Through the making of this one picture, the owner of the store, Paige Carter, became my set decorator, and has worked on every single production since.

There’s an anecdote about Millais’ model, a version of which is posted on the website of the Tate. She posed in a bathtub of water and in the process got extremely cold and then sick. I didn’t know that story specifically at the time, but I was preoccupied with the water being warm enough. The night before the shoot, we did a pre-light, and also tested keeping the water temperature up, and we wound up overtaxing the building’s boiler. As we were getting ready to leave for the night, someone smelled smoke. This turned into a bit of a fiasco. The fire department was called. And a story ran in the local newspaper the following day. The good news is we did not burn down the building.

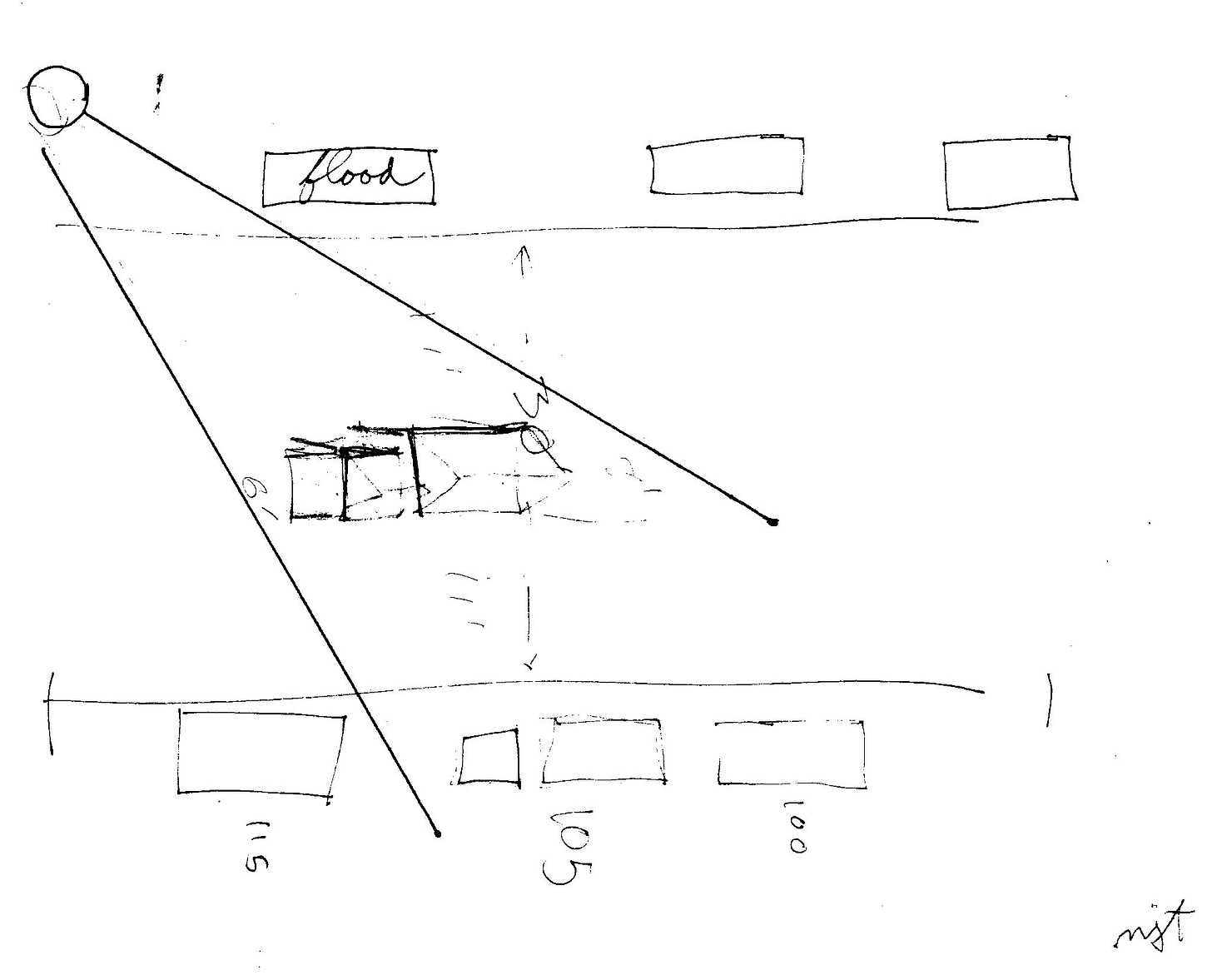

The following day, we moved forward with shooting the picture. I tried two different set-ups, with different camera positions. In the first, the Ophelia figure would be poised at the bottom of the staircase contemplating entering the water. In the second, she’d be submerged and floating.

Nick had built a small platform to support the subject’s weight. I liked that the platform allowed her to float in a bit of an unnaturally elevated way, so that she almost appears to be levitating out of the water.

We shot many frames of the first version, with the subject standing at the edge of the water at the bottom of the staircase. It wasn’t quite working. Then we had her lay on the platform in the water. I first had her look straight up, but then had her turn her gaze just slightly toward camera. I looked at her expression in the ground glass, and knew immediately: this was it.

On March 25, 2001, The Sunday NY Times ran a piece by Nelson Hancock about the making of the picture, featuring the finished image. This was actually the first context in which the picture was seen publicly. It then wound up as the cover of the Twilight monograph, and on the poster for the show, and really became a touchstone for that series and that chapter of my work — and making the picture really opened my eyes to the seemingly limitless possibilities that constructing and lighting sets on the soundstage offered, particularly when shooting with an 8 x 10 camera. Every interior in Beneath the Roses (2003-2008) would be designed, constructed, and realized on the MASS MoCA stage in the following years.

Posts on the Crewdson Trail Log are written and assembled by Juliane Hiam. This piece was based on conversations with Gregory, Nick Thielker, Daniel Karp, and archival materials.

I’ve loved this image for so long! Incredible to hear the story behind it and see the bts. 🙏

Cool stuff! I really like the contact print where she's contemplating stepping into the flood, too. A different but compelling mood.